Nirmolendu Goon and Hassanal Abdullah

Nirmolendu Goon and Hassanal Abdullah

Hassanal Abdullah

Nirmolendu Goon and Hassanal Abdullah

Nirmolendu Goon and Hassanal Abdullah

|

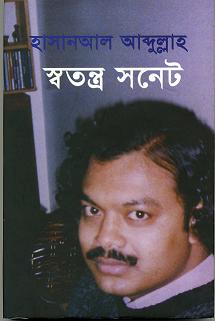

A Poet- Explorer's Voyage to the Seaby Jyotirmoy DattaA seventeenth century European traveler claimed in his travelogue that Bengal, not Egypt is the biggest, and most fertile delta in the world. The orchards of Egypt are devoid of Bengal's jackfruit-mango-sugarcane, the lakes and rivers deprived of the range of delicious fishes of Bengal, and finally the charmed appeal, and warm lucid eyes of the delicately olive Bengali femininity was no where to be found outside of Bengal. "There are thousand doors open to enter Bengal," wrote Francios Tevernier, "but none to depart through", he concluded. What would T say if he were to come back in the present day Bangladesh? If he had to face the two opposing females ruling the political domain, and their bomb attacks; he surely would have desperately attempted to escape. But Bangladesh has also brought amazing renaissance in the fields of women's education, agriculture, arts, music, dances, and academia in the last thirty years. This positive inclination of Bengal would have surely convinced T that, with the boon of the two major rivers of the subcontinent this delta has finally arrived at the door unfolding its potentials. It hasn't even been three decades since its independence--hundred and twenty million human beings crammed in 56,000 sq. miles--weighed down by the highest rate of population per sq. mile in the globe--Bangladesh has still been able to become self sustained in agriculture, rural development, spread of education, and expansion of literary activities. During the period of domination and exploitation under the hegemony of West Pakistan, Bangladesh was merely an export based state, its backwardness in per capita income, life expectancy, nutrition, health care, and the total infrastructure was alarming in comparison to Northern provinces like Sindh and Punjab. But today the scenario is quite different. Bangladesh is beating not only Pakistan, but India, in its growing rate of female literacy. Bangladesh, today, is engaged in a race that pulls the country towards two completely opposite poles--growing Islamic fundamentalism on one end, and the evolving humanism of Bengali literature on the other. The fertile, and delicate delta of Ganges, and Brahmaputra is trembling in this conflict. The offshoot of Hasina-Khaleda conflict is giving birth to growing migration, and constantly giving birth to green-Bengals in Malay-Bahrain-Addis-Ababa, in Humburg-New York-London. In those colonies across the sea, stores are named--Lotus, or Dhanshiri, music tapes of Nazrul-Tagore songs are circulated, and for thousands of immigrants very few Bengali weekly are coming out with titles such as, 'Purbasha', or 'Ushar Alo' or 'Gopalganj Harkara'. Many countries have become sovereign within the last fifty years, but no where else had taken place such an uprising over the issues of language, and literature. No other place in the world has had moments like 21st February, 1951; that marks a struggle and self sacrifice for the cause of Bangla language, a moment that is completely different than the moments of independence partially delivered by the French or the British colonizers. In the face of the globe, Bangladesh is the converging point of politics and culture, it is the engagement point between medievalism and post-modernism. It is my pleasure to be witnessing this process through the journey of an evolving poet. Hassanal Abdullah was born in Bangladesh, Gopalganj thana, and Gopinathpur village, prior to independence, in 1967. His father Maulana Nawsher Ali Mia was severely injured by the Pakistani Army during independence movement in 1971, and died after few months later. Hassan's mother's strong attachment to religiosity, however, had not been influenced by any external forces. I have met Zahura Khatun in New York; to me it seemed like she embodied the terracotta that has been produced by the psychological, and physical application of forces over the soft terrains of Bengal, a force alien to its soil, a force of religious preachers originating from the hot sand of Arabia. Hassanal Abdullah has taken his time to break that mold of baked clay. A student of mathematics at the University of Dhaka, he migrated to New York at the age of twenty three, a new life started for him: driving cabs, writing poetry, and math courses at the Hunter College. Is triumphant poems a winning of the lottery? Or is it the fruits of dedication, and practice? Some are the Lords of mature styles from the very beginning, they gain fame swiftly, like Shakti Chattopadhay, or Samar Sen. And there are some who evolve more slowly, they open up like a butterfly from a moth. I only realized the strength of Shudindranath's dedication towards poetry after looking at the note books he kept during his adolescence; in the beginning of those notebooks were prayers to the God written in his neat script. Shudindranath's preparation for writing poetry can be compared to Milton, Dutta studied Sanskrit in Varnasi, traveled through Europe with Rabindranath Tagore; maybe he was a little to learned for a poet, a little too attractive, a little too wealthy. Hassanal Abdullah in many ways is opposite to Shudindranath, even though the effort, endeavor, focus of both poets are easily comparable. Shudindranath was tall, very fair, and super class-conscious even from his time. Hassanal Abdullah, on the other hand, is the new spark from the soil of Bengal, and his face most definitely resembles Nazrul's. When he discusses poetry passionately, his round eyes become animated framed by his curly hair. He hasn't been to Mesopotemia's Palton, but driven cabs in the crazy streets of Manhattan, he's got guts. What he has even more is determination. His pen is indefatigable, poetic emotions, and comic cohabit in his writing, he moves on like a desperate peasant who relentlessly ploughs through the land full of stone and weeds. May it be a soft delta to cross or a sea of stone, Hassanal Abdullah is always moving forward, inexorable, driven by vigorous strength. His 'Swatantra Sonnet' is written, as if, under a spell, intoxicated by the effort to invent a new form, sometimes the Sonnet goddess bestowed upon him more than one poems per night. Those who are lucky, has seasons in their lives, when they actually do not write, but they are being possessed to write. It is the same magic charm that was in action in Jibanananda's 'Ruposhi Bangla' and Rainer Maria Rilke's Duino verses. Is this what I have mocked as lottery winning of poetry? Well, as a land that is not ploughed properly cannot produce any crop even with the help of plenty of rain; similarly, a poet whose inside is not prepared to produce poetry will never be able to produce 'Sonnets to Orpheus' even if he was touched by the magic rod of imagination. Hassanal Abdullah has perfected the rules of rhyme for a long time, and that's why 130 sonnets have come down on the pages via his pen. I do not know, if there is anyone else in his generation who has gone up on a hike over the mountain of poetry, step by, step like Hasan has. Everest was not conquered in one day, but the devi of Bangla poetry has certainly put a garland of victory around HassanAl Abdullah's neck. This poet is always revolving, he is experimental. He is never self satisfied; he is looking, he is breaking himself, and diligently reading Bangla, English, and global poetry. These two books are the maps of Hassanal Abdullah's voyage on the sea of poetry. He has come a long way--but I am sure that he will go much further. Translated from Bengali by Rubaiyat Hossain |